A new study published in Nature Medicine revealed that neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) patients who have slow-growing brain tumors may have promising results with immunotherapy treatments.

Nearly 100,000 people in the United states have NF1, a genetic disorder that can cause issues in many areas of the body, including the skin, eyes, bones, and brain. These patients oftentimes go on to develop cancerous brain tumors called glimoas, which are particularly lethal and untreatable.

Nearly 100,000 people in the United states have NF1, a genetic disorder that can cause issues in many areas of the body, including the skin, eyes, bones, and brain. These patients oftentimes go on to develop cancerous brain tumors called glimoas, which are particularly lethal and untreatable.

Despite the fact that several cases of NF1 occur in the U.S., clinicians know very little about the process that takes place when glimoas form in NF1 patients. Researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons recently led a study to learn more about NF1-gliomas and how they might be treated.

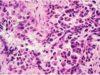

The study involved analyzing tumors from 56 NF1-glioma patients. Researchers learned how the tumor changed genetically (DNA cell sequence), epigenetically (DNA modifications), and immunologically (immune responses to the tumor).

Some of the study’s findings were not surprising. For instance, the gene TP53, which helps to stop tumors from forming, was not working properly in many of the tumors that were analyzed. The team also discovered several pathways that the tumors used in order to sustain their growth. These results will be helpful in assisting future research teams to possibly come up with treatments for NF1-gliomas.

Some of the study’s findings were not surprising. For instance, the gene TP53, which helps to stop tumors from forming, was not working properly in many of the tumors that were analyzed. The team also discovered several pathways that the tumors used in order to sustain their growth. These results will be helpful in assisting future research teams to possibly come up with treatments for NF1-gliomas.

But the findings that were most insightful are those that could have “immediate clinical repercussions for NF1 patients,” said Antonio Lavarone, senior author of the study. According to Anna Lasorella, MD, and co-author of the study, “approximately 50 percent of the slow-growing NF1 gliomas contained large numbers of T-cells that have the ability to destroy cancer cells.” This finding was surprising to the team, and it allowed them to conclude that NF1-gliomas could respond well to certain cancer treatments that already exist.

That the tumors contained a large amount of T-cells signals that NF1-glioma patients may respond well to immunotherapy treatments in particular.

Immunotherapy works to intervene in immune system malfunctions that involve T-cells. T-cells typically serve to get rid of cells in the body that aren’t acting normally, either due to viral infection or malignancy. When tumors occur, it usually signals that the body’s immune system isn’t working properly. This happens most often when the tumor finds ways to either evade or shut off T-cells. Immunotherapy treatments are designed to get T-cells to work properly again or to stop the tumor from evading the immune system’s defenses.

Immunotherapy works to intervene in immune system malfunctions that involve T-cells. T-cells typically serve to get rid of cells in the body that aren’t acting normally, either due to viral infection or malignancy. When tumors occur, it usually signals that the body’s immune system isn’t working properly. This happens most often when the tumor finds ways to either evade or shut off T-cells. Immunotherapy treatments are designed to get T-cells to work properly again or to stop the tumor from evading the immune system’s defenses.

Researchers did note that more aggressive NF-1 gliomas that grow more rapidly were excellent at avoiding the immune system, so patients with those types of tumors will not likely respond to immunotherapies. But because those fast-growing tumors had a large number of DNA errors, they might respond to treatments that create even more of those errors. The idea behind this treatment is that the cells will ultimately be so damaged that they would no longer be able to reproduce, which may stop or stunt the tumor’s growth.

Treatments that follow this protocol include therapies like chemotherapy and radiation, which means that especially aggressive NF-1 glimoas could respond well to those treatments, while slow-growing NF-1 gliomas may respond well to immunotherapies.