A recent study published in Nature Medicine reveals new ways to determine which cancer patients will respond best to immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors. This kind of therapy has shown great potential in effectively removing malignancies in about 20 to 40 percent of patients with cancers like melanoma, but there are still many patients whose cancer it does not eliminate. Researchers suggest that these poor outcomes may have to do with the arrangement of immune cells both inside the tumor and around it. By using the data from the study, doctors can alter the patients’ immune responses to increase the chances that the treatment will take, and ultimately end up increasing their survival.

A recent study published in Nature Medicine reveals new ways to determine which cancer patients will respond best to immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors. This kind of therapy has shown great potential in effectively removing malignancies in about 20 to 40 percent of patients with cancers like melanoma, but there are still many patients whose cancer it does not eliminate. Researchers suggest that these poor outcomes may have to do with the arrangement of immune cells both inside the tumor and around it. By using the data from the study, doctors can alter the patients’ immune responses to increase the chances that the treatment will take, and ultimately end up increasing their survival.

Immunotherapy with Checkpoint Inhibitors

Although the immune system works to fight off foreign substances and infections in the body, it sometimes backfires against cancerous cells. In order for the immune system not to attack the body’s own tissues, “checkpoint proteins” exist in order to keep immune responses to a minimum. Cancers are thus oftentimes able to evade the body’s immune system by giving off these checkpoint proteins, which keeps T-cells from attacking the tumor.

Researchers have developed a new type of cancer-fighting drug known as checkpoint inhibitors that guard against the checkpoint proteins that hinder the body from fighting cancer. These drugs, Keytruda and Opdivo, for example, enable T-cells to actively attack cancerous cells.

But as Matthew Krummel, PhD, professor of pathology and senior author of the study, points out, drugs like Keytruda and Opdivo are not enough. Although these drugs effectively block checkpoint proteins, they don’t necessarily stimulate the most effective response from T-cells. So the team worked to determine which types of cells within the tumors might actually activate the T-cells that attack cancer. They thus began to “recruit” allies in the tumor to determine who were the “good and bad partners within the immune system.”

What the Study Revealed

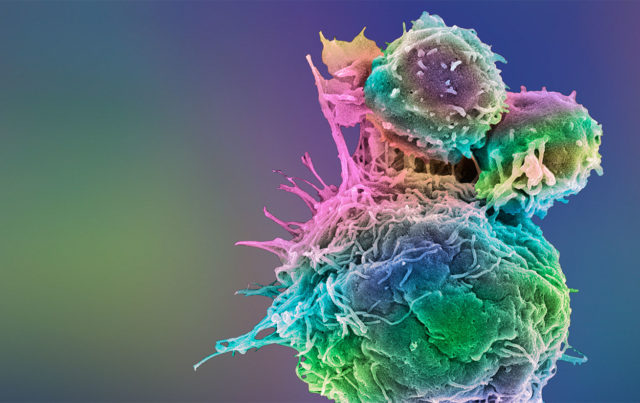

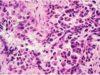

The study, “A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments,” which used experiments in both mouse and human tumor models, showed that certain kinds of immune cells, called stimulatory dendritic cells, (SDCs), are necessary in order for T-cells to give off a more forceful response. When those cells were not present, T-cells could not respond effectively to the checkpoint inhibitor drugs. But even still, in order for those SDCs to be active and successful within the tumors, they need the help of NK (natural killer) cells, which typically serve as the first line of defense in discovering cancer cells.

The study, “A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments,” which used experiments in both mouse and human tumor models, showed that certain kinds of immune cells, called stimulatory dendritic cells, (SDCs), are necessary in order for T-cells to give off a more forceful response. When those cells were not present, T-cells could not respond effectively to the checkpoint inhibitor drugs. But even still, in order for those SDCs to be active and successful within the tumors, they need the help of NK (natural killer) cells, which typically serve as the first line of defense in discovering cancer cells.

Using tumor samples from both melanoma patients and mouse models, the team determined that NK cells were the core partners within the tumor community of immune cells. They determine the amount of SDCs inside the tumor by giving off a “messenger molecule” called cytokine. They thus help to activate the SDCs as well as help them to flourish. Researchers found that in melanoma patients, the amount of SDCs and NK cells strongly correlated with the patient’s receptiveness to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which means that the communication between the two within the tumor is directly related to the patients’ outcome.

Krummel writes that scientists have always known that natural killer cells are crucial in helping to fight off cancer by directly attacking it. What’s new about this discovery, though, is that researchers have now uncovered NK cells’ ability to actually communicate with other immune cells, something that is perhaps even more important than just eliminating threats directly.

How the Study Benefits Cancer Patients

Kevin Barry, PhD, lead author of the study, explains that the results are exciting because they will allow new immunotherapies that target NK cells to potentially be more successful. If scientists can find a way to increase the NK cells in tumors, then SDC levels might be increased, which would eventually yield an improved response to both current immunotherapies and ones that are still being tested.

The study’s findings might also be used in helping to find biomarkers in the blood that show whether a tumor has NK cells and SDCs. This would help physicians to identify patients who are mot likely to respond to immunotherapy. As Barry writes, currently, physicians depend on biopsies or other invasive procedures that obtain samples from the tumor to help reveal the kinds of cells it contains. Finding these associations with a blood test would be a much less invasive and much more efficient way to learn about a patients’ tumor and come up with an effective treatment plan.

The study’s findings might also be used in helping to find biomarkers in the blood that show whether a tumor has NK cells and SDCs. This would help physicians to identify patients who are mot likely to respond to immunotherapy. As Barry writes, currently, physicians depend on biopsies or other invasive procedures that obtain samples from the tumor to help reveal the kinds of cells it contains. Finding these associations with a blood test would be a much less invasive and much more efficient way to learn about a patients’ tumor and come up with an effective treatment plan.