The mammogram screening process in the United States has been the same for nearly twenty years. Women between the ages of 45 and 50 begin getting a yearly, routine x-ray exam to check for any lumps or changes in the breast. Although the process has prevented many cases of breast cancer, it’s not fool proof, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) thinks it may be time for some changes.

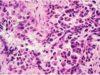

After a radiologist performs a mammogram, they are required by law to provide the patient with a report that details any issues found during the exam. But there is one “issue” that radiologists are not currently required to report: breast density. Nearly 50% of all mammograms uncover “dense breasts,” which means that the woman has less fatty tissue and more fibrous connective or glandular tissue. The dense breast tissue appears white or gray on the x-ray image, which can make it difficult for the radiologist to decipher. It may even become harder for them to spot cancerous tumors, and it ultimately creates a less accurate screening. Aside from the issues it creates during the screening process, breast density is also a risk factor for developing breast cancer. It’s something every patient should know about.

After a radiologist performs a mammogram, they are required by law to provide the patient with a report that details any issues found during the exam. But there is one “issue” that radiologists are not currently required to report: breast density. Nearly 50% of all mammograms uncover “dense breasts,” which means that the woman has less fatty tissue and more fibrous connective or glandular tissue. The dense breast tissue appears white or gray on the x-ray image, which can make it difficult for the radiologist to decipher. It may even become harder for them to spot cancerous tumors, and it ultimately creates a less accurate screening. Aside from the issues it creates during the screening process, breast density is also a risk factor for developing breast cancer. It’s something every patient should know about.

The current regulations state that any information about breast density must be included in a report to the patient’s physician, but not in the report given directly to the patient. Oftentimes, doctors will not follow up with a patient if the test results are benign, and if patients are getting letters sent home, they generally will not reach out to their doctors themselves. This means that women who have dense breasts may not even know.

The new standards proposed by the FDA would require that women get information about their breast density directly. If a woman is found to have “dense breasts” that could alter their screening results or increase their risk of breast cancer, they must receive some sort of notification.

Does having high breast density change your cancer screening guidelines?

Although the FDA believes that women need to be aware of their breast density, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they need to take any further action. Christopher Lee, professor of radiology and breast imaging specialist the University of Washington School of Medicine says that “informing women is the right thing to do.” But whether or not a woman gets additional screening is dependent upon the details of each case. For instance, in some states, like Connecticut, having dense breasts automatically entitles a woman with dense breasts to an ultrasound or MRI along with their yearly mammogram.

Although the FDA believes that women need to be aware of their breast density, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they need to take any further action. Christopher Lee, professor of radiology and breast imaging specialist the University of Washington School of Medicine says that “informing women is the right thing to do.” But whether or not a woman gets additional screening is dependent upon the details of each case. For instance, in some states, like Connecticut, having dense breasts automatically entitles a woman with dense breasts to an ultrasound or MRI along with their yearly mammogram.

But further screenings are usually only recommended for women who have additional risk factors, such as a family history of cancer, the BRCA gene mutation, or older age. According to Lee, if anything, having dense breasts is a good reason to explore any other risk factors. Rather than automatically receiving additional screening, a woman can consult with their doctor to determine if they find it necessary. Assuming that high breast density requires additional screening could cause consequences like false positives, high costs, and excess anxiety, so it’s important to weigh the factors on a case-by-case basis.