Among the several strategies oncologists use to treat cancer, there has never been one quite like the new fecal transplant method, proposed by a few research teams at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). The therapy is currently being tested in clinical trials, and it’s been shown to halt the growth of tumors in patients who previously did not respond to immunotherapy drugs.

The fecal transplant involves taking a stool sample from a healthy donor and placing it into the gut of a cancer patient. Theoretically, the gut microbes from the healthy patient will help to create a a stronger microbiome in the cancer patient’s gut, which will enhance their overall health. Researchers have already been investigating the use of fecal transplants to help treat colon infections of the bacterium Clostridium difficile, but this is the first time they are being considered as a way to treat cancer.

The fecal transplant involves taking a stool sample from a healthy donor and placing it into the gut of a cancer patient. Theoretically, the gut microbes from the healthy patient will help to create a a stronger microbiome in the cancer patient’s gut, which will enhance their overall health. Researchers have already been investigating the use of fecal transplants to help treat colon infections of the bacterium Clostridium difficile, but this is the first time they are being considered as a way to treat cancer.

The method is currently being tested in two different studies, both of which are in the very early phases. Only a small number of patients have been given the treatment and they have only been monitoring them for a few months so far. But the early results are promising. Jennifer Wargo, a melanoma researcher at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, said that “this is the first clinical evidence that you may have an impact on antitumor immunity and potentially even responses.” Wargo is leading a trial with the method that is just getting started.

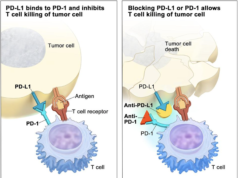

The studies rely on immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors. These drugs help to block PD-1, a protein on the surface of immune cells known as T cells. The protein usually stops the immune system’s ability to fight off foreign antibodies, and tumors know how to incite PD-1 to protect themselves so they can keep growing. Checkpoint inhibitor drugs have been able to open up ways for the immune system to attack, putting many cancer patients into remission. But there are still many cancers that do not respond, leaving researchers to figure out how they can improve the efficacy.

Studies in the past few years have shown a possible correlation between treatment response and the bacteria, viruses, and other microbes in the gut — known as the microbiome. Scientists have found that gut microbiomes differ between patients who respond to immunotherapy and those who don’t. They also discovered that patients who were on antibiotics (which are known to wipe the gut of all positive bacteria) shortly after receiving checkpoint inhibitors responded even less.

Studies in the past few years have shown a possible correlation between treatment response and the bacteria, viruses, and other microbes in the gut — known as the microbiome. Scientists have found that gut microbiomes differ between patients who respond to immunotherapy and those who don’t. They also discovered that patients who were on antibiotics (which are known to wipe the gut of all positive bacteria) shortly after receiving checkpoint inhibitors responded even less.

Experiments conducted on mouse models have shown that immunotherapy drugs worked better after the mice received a fecal transplant from human patients whose tumors did respond after receiving the drugs.

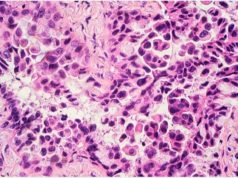

One study conducted by Gal Markel and Ben Boursi at Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, Israel, took stool samples from two patients with metastatic melanoma. These patients saw their tumors disappear after receiving PD-1 drugs. The research team thus took their feces using a colonoscopy and transferred them to three patients with the same kind of cancer whose tumors did not respond to the checkpoint inhibitor drugs. The patients also received oral pills with the donors’ dried stool.

One study conducted by Gal Markel and Ben Boursi at Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, Israel, took stool samples from two patients with metastatic melanoma. These patients saw their tumors disappear after receiving PD-1 drugs. The research team thus took their feces using a colonoscopy and transferred them to three patients with the same kind of cancer whose tumors did not respond to the checkpoint inhibitor drugs. The patients also received oral pills with the donors’ dried stool.

The researchers saw the gut microbiomes of all three patients change to match those of the patients who did respond to the treatment. Two of the patients who received the fecal transplant experienced a response to the OD-1 drugs. One patient saw their tumor shrink, but experienced two new tumors months later. Another patient saw their tumors shrink and is still doing well 7 months later. Studies show that this transplant possibly made “cold” tumors become “hot,” or more visible to the immune system.

Researchers are continuing to test this method to figure out exactly how it works, determine safety, and improve efficacy.