A study led by Dr. Joshua Brody of Icahn School of Medicine in New York City revealed that a new immunotherapy treatment involving vaccines has been successful at treating lymphoma. The results were published in Nature Medicine, and they show that several patients in the trial experienced a reduction in their tumor.

A study led by Dr. Joshua Brody of Icahn School of Medicine in New York City revealed that a new immunotherapy treatment involving vaccines has been successful at treating lymphoma. The results were published in Nature Medicine, and they show that several patients in the trial experienced a reduction in their tumor.

Brody is the director of the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program at the Icahn School of Medicine. His team there is working with a vaccine that contains two immune stimulants. After injecting the stimulants directly into the tumor, the team sees “all of the other tumors just melt away.” The vaccine works by showing the immune system where the cancerous cells are so it can begin to attack them.

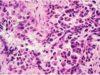

Eight out of eleven patients in the trial saw their tumor either decrease in size or disappear altogether. Six patients also experienced a stop in their disease progression for 3-18 months. Three patients had a significant regression or went into full remission.

The study’s results had enough potential to allow for an expanded study, which began in March. The new study will continue to test lymphoma and also include breast and head and neck cancers. It will also add another immunotherapy protocol into the mix called checkpoint inhibitor drugs. Studies with mice suggested that the vaccine combined with the inhibitor drugs could produce better results.

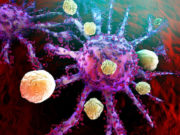

Immunotherapy has had success in treating many cancers, but most protocols are a bit different from this one. Usually, immunotherapy approaches target T-cells, which are in charge of warding off pathogens in the body. Checkpoint inhibitor drugs alert T-cells of the presence of cancer cells so that they can do their job.

Immunotherapy has had success in treating many cancers, but most protocols are a bit different from this one. Usually, immunotherapy approaches target T-cells, which are in charge of warding off pathogens in the body. Checkpoint inhibitor drugs alert T-cells of the presence of cancer cells so that they can do their job.

Checkpoint inhibitor drugs are widely known as “Jimmy Carter drugs,” since they successfully treated the former president’s advanced melanoma. They have been effective drugs to treat many kinds of cancers, but research is still being done to try and improve their efficacy.

This new vaccine protocol focuses not on T-cells, but on dendritic cells, which are necessary for guiding T-cells to destroy foreign invaders. Brody calls T-cells the immune system’s “soldiers,” and dendritic cells the immune system’s “generals.” Brody and his team are attempting to “mobilize these immune generals to tell the soldiers what to do.”

Patients in the trial were given 9 injections of the immune stimulant every day, which alerted dendritic cells to the presence of cancer cells. Once the cancerous cells were grouped together, the patients were then given 8 injections of an additional stimulant that then activates the dendritic cells. This process allows T-cells to effectively destroy any visible cancer cells in the body.

The word “vaccine” throws many people off, as they imagine vaccines to be preventative like the flu shot or the MMR. Those kinds of vaccines work to instruct the immune system how to ward diseases off at a later time. The cancer vaccine is not preventative, but therapeutic. Brody and his team are trying to use the vaccines to destroy the disease even after it’s already present in the body.

The word “vaccine” throws many people off, as they imagine vaccines to be preventative like the flu shot or the MMR. Those kinds of vaccines work to instruct the immune system how to ward diseases off at a later time. The cancer vaccine is not preventative, but therapeutic. Brody and his team are trying to use the vaccines to destroy the disease even after it’s already present in the body.

The study has shown great promise in treating patients with lymphoma, but it still has a long way to go to confirm its success and possibly treat other cancers.